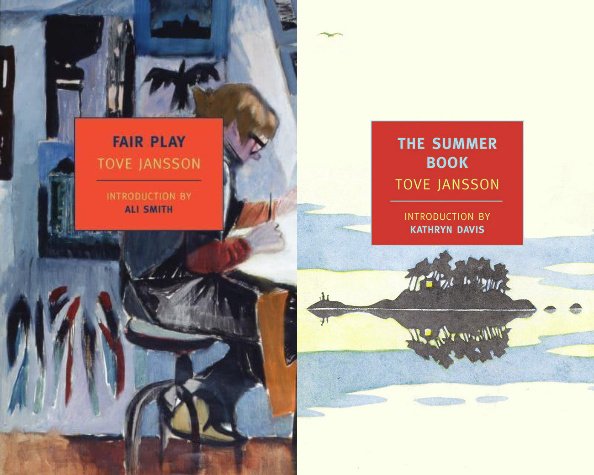

Tove Jansson, Fair Play and The Summer Book

/They lived at opposite ends of a large apartment building near the harbor, and between the studios lay the attic, an impersonal no-man’s-land of tall corridors with locked plank doors on either side. Mari liked wandering across the attic; it drew a necessary, neutral interval between their domains. She could pause on the way to listen to the rain on the metal roof, look out across the city as it lit its lights, or just linger for the pleasure of it.

They never asked, “Were you able to work today?” Maybe they had, twenty or thirty years earlier, but they’d gradually learned not to. There are empty spaces that must be respected—those often long periods when a person can’t see the pictures or find the words and needs to be left alone.

(From “Videomania” in Fair Play)

Tove Jansson knew these empty spaces well. She came from a family of artists and, in addition to being a writer, was serious about her painting and illustration. She and her partner of more than forty years, visual artist Tuulikki Pietilä, spent winters in Helsinki and nearly thirty years of long summers alone together on the tiny island of Klovharun in an archipelago off the coast of Finland.

Jansson’s books for adults, beloved to a somewhat smaller crowd than those who love her enchanting, impossible Moomins and their friends, pay close attention to the intricate textures and spaces between and around close relationships. Although she’s so different from Jessica Au, whose Cold Enough for Snow I looked at a couple of months ago as part of this project, she also sometimes offers a similarly oblique angle of approach, the pressure of two fiercely separate beings in a close space, though with Jansson, the pairs in the novels Fair Play and The Summer Book are so integrated into their surroundings that they become a part of the landscape, and the spaces between feel them feel both generous and inexorable.

Fair Play

The two women at the heart of Fair Play—Mari, a writer, and Jonna, a visual artist—are longtime partners who live down the hall from each other and sometimes alone together on a remote island of the Finnish archipelago. People often say that not much happens in Jansson’s books, but in fact everything happens. Life happens. Mari and Jonna make art and fail to make art, invite in visitors and protégés, create and maintain their rituals around shared and separate spaces, and travel—all in 17 very short stories centering sometimes around dramatic but ordinary natural events, and sometimes around moments of connection, entanglement, forbearance, and the tension that comes from the unsaid.

Looking back at Au, I think how much narrative tension in Cold Enough for Snow comes from the mother and daughter’s subterranean efforts to communicate with each other, and from the slow sadness of that impossibility. But as a reader, I never stop wishing for it and feeling the sadness of those spaces in between.

In Jansson, though, part of the beauty is in the ways that the characters accept everything they cannot and should not say to each other, as in this passage when Jonna is in one of those blocked/fallow/inevitable/painful moments when an artist is not working and the next project isn’t yet ready to emerge:

The summer had moved into June. Slowly, thinking Mari didn’t notice, Jonna went from window to window, tapped the barometer, walked out on the slope or out on the point, came in again with comments about things that needed attention, complained about the gulls screaming and copulating to drive a person crazy, and spoke her mind about the local radio, which had the most idiotic programs—for example, about amateurs who had shows and thought they were God’s gift to art. And the weather was implacably beautiful the entire time.

Mari said nothing. What could she say?

Finally Jonna got busy. She built up her great unassailable barricade against work, against the agony of work. With small, polished tools she began shaping exquisite small objects of wood, tinier and tinier, more and more beautiful. She visited the islands to the west looking for juniper; she walked the shoreline gathering unusual kinds of driftwood, odd shapes that might give her an idea. She arranged it all on her workbench in symmetrical piles, smaller ones, larger ones, and every piece of sea-polished wood had its own special potential to keep her from making pictures.

Oh, Tove Jansson! There’s a BBC documentary about her life on the island that shows her swimming through the sea with a crown of flowers, wearing an expression of such delight that it’s almost impossible to imagine on an adult, let alone one with this level of understanding of how impossible it is to intervene. The passage above embodies procrastination through actions and objects and the reported dialogue of Jonna’s complaints about birds and amateur artists, both driving her crazy with their exuberant life, which can feel so offensive in that bitter furious state of not-working.

And it’s funny too. The implacably beautiful weather, that “every piece of sea-polished wood had its own special potential to keep her from making pictures.”

There’s the sense that at least some of the material in Fair Play could be memoir, but the omniscience that moves from character to character, without needing to tell us every single thing, allows Jansson to follow her natural inclinations and evade some of the great temptations of the memoir: self-justification, self-delusion, extensive analysis of one’s own or other people’s motives. Phillip Lopate’s essential instruction that the memoirist must create the self as a character can also often get way out of hand in practice (I realize that all of these potential faults are also some of the occasionally wicked delights of the memoir—we are wondering if the writer knows just how much she is revealing about herself, and whether we should look away, and we are possibly reassuring ourselves that she does know what she’s revealing because she’s wildly brave, and at the same time we are reminded of all of our own worst qualities in a very comforting fashion. Or maybe that’s just me…)

Jansson always refuses the sentimental or invasive. Mari and Jonna allow each other empty spaces and privacy, and the book gives them privacy too, which is at least in part an artistic decision, though of course that’s not all there was to it. For a long time, as Ali Smith mentions in her introduction to the NYRB edition, Pietilä was left out of her public biography.

The Summer Book

In another great Jansson novel comprised of very short stories, The Summer Book, published a decade earlier, in 1972, the child Sophia and her grandmother navigate the world by themselves on a similarly remote Finnish island. Sophia’s mother has recently died, and her father appears to be in the house but is a shadow, hardly on the page. Grandmother and granddaughter explore their island, fight, unexpectedly look after each other, and hold their own as equals in battle.

The novel investigates life after a mother/daughter’s death, barely referring to that death, focusing on the isolation and drama of the island, age and youth. The concise stories are heartening, delicious, prickly, unsentimental, exacting. The emotional movement again often comes from what they don’t say to each other, or from changes of subject and shifts in the tone.

In “The Pasture,” Grandmother and Sophia walk to the village, and on the way Sophia asks her grandmother what Heaven looks like, and Grandmother says it’s like the pasture they’re walking through. They look at the pasture: “it was very hot, the road was white and cracked, and all the plants along the ditch had dust on their leaves. They walked into the pasture and sat down in the grass, which was tall and not a bit dusty. It was full of bluebells and cat’s-foot and buttercups.” And then Sophia asks if Heaven has ants. “’No,’ said Grandmother, and lay down carefully on her back.”

The story starts out in Sophia’s POV, but moves to Grandmother’s as she tries to “sneak a little sleep” despite the insects. Jansson doesn’t say that Sophia gets tired of waiting but instead writes, “Sophia picked some flowers and held them in her hand until they got warm and unpleasant; then she put them down on her grandmother and asked how God could keep track of all the people who prayed at the same time.”

Grandmother tries to evade this by suggesting God has secretaries, and they begin to battle over questions like whether angels can fly to Hell. When Grandmother says that angels can visit their friends and neighbors there, Sophia is furious:

“Now I’ve got you!” Sophia cried. “Yesterday you said there wasn’t any Hell!”

Grandmother was annoyed and sat up angrily.

“And I say exactly the same thing today,” she said. “But this is just a game.”

“It’s not a game! It’s serious when you’re talking about God!”

“He would never do anything so dumb as make a Hell.”

“Of course He did.”

“No He didn’t!”

“Yes He did! A big enormous Hell!”

Because she was mad, Grandmother stood up much too quickly, and the whole pasture started spinning around and she almost lost her balance. She waited for the giddiness to stop.

“Sophia,” she said, "This is really not something to argue about. You can see for yourself that life is hard enough without being punished for it afterwards. We get comfort when we die. That’s the whole idea.”

This explanation doesn’t work for Sophia at all, and the argument spirals more and more out of control as Grandmother begins to insist, “You can believe what you like, but you must learn to be tolerant.”

Eventually, they are fighting about whether Grandmother shouting “I’ll let you believe God damns people and you let me not” counts as swearing, and then they aren’t speaking at all:

They were no longer looking at each other. Three cows came down the road, switching their tails and swaying their heads. They passed slowly by in a swarm of flies and walked on towards the village, with the skin on their rear ends puckering and twitching as they went. Then they were gone, leaving nothing but silence.

Finally Sophia’s grandmother said, “I know a song you don’t know.” She waited for a minute, and then she sang—way off key because her vocal chords were crooked:

Cow pies are free,

Tra-la-la

But don’t throw them at me.

Tra-la-la

For you too could get hit

Tra-la-la

With cow shit!

“What did you say?” Sophia whispered, because she couldn’t believe her ears. And Grandmother sang the same really awful song again.

Sophia climbed over the ditch and started toward the village.

“Papa would never say ‘shit,’” she said over her shoulder. “Where did you learn that song?”

“I’m not telling,” Grandmother said.

They came to the barn and climbed the stile and walked through the Nybonda’s barnyard, and before they got to the store under the trees, Sophia had learned the song and could sing it just as badly as her grandmother did.

And that’s the end of the chapter. In craft terms, it’s not hard to see what Jansson’s doing: she’s stripped out explanation and certain kinds of transitions and substituted the tangible qualities of the moment for silences. The narrator sometimes closely inhabits both characters but is not either character, and there is no special pleading. It gives a very good idea of their relationship and of Grandmother’s child-rearing strategies.

But craft only takes you so far in accounting for the breathtaking mysteries of Jansson’s books, which are—like the weather as Jonna wrestles with the painting she’s not doing, or the hot day in which a cow pasture can look like Heaven to a pair of bereaved, quarrelsome people who rely on each other completely—implacably beautiful.