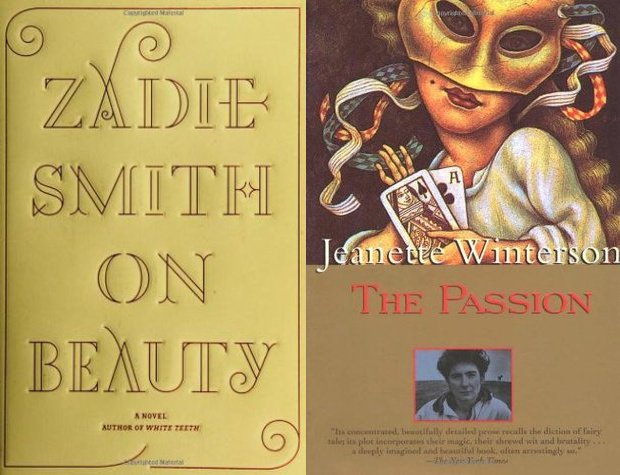

Zadie Smith, On Beauty, and Jeanette Winterson, The Passion: Domesticity and Wildness

/Right now I’m teaching On Beauty and The Passion to an advanced novel-writing class and so have been rereading both novels. Maybe one of the reasons I love them so much is that they are about errant or unexpected love and that they each, in their own way, subvert domesticity. They remind me of my childhood family parties. Back when my parents were alive, we used to celebrate all the extended family birthdays, and every other occasion, with as many family members as we could gather, friends, and people invited on the spur of the moment. Not many of my father’s university colleagues were invited, even before the divorce, since according to my mother the mess of our family and chaos of the house embarrassed him. All the strange art covering the walls, the hoarded and treasured supplies, and then, at parties, fiery words and messy apologies, someone crying in a bathroom or hallway, people embracing afterward and assuring everyone of their love. Immersive family theater.

In my early twenties, for some reason that I now can’t recall, I took both my then-husband and then-girlfriend to one of these events. In a family that managed quite a lot of happiness and acceptance, despite a fair bit of mental illness and addiction, the general response was to greet us with a little eye-rolling and to enfold us in the preparation of one of our multi-hour feasts (so much drama requires a lot of nourishment). I rarely saw anything like our family’s version of domesticity in the literature I read, though my then-husband and I were very fond of Gregory Corso’s “Marriage” (“Should I get married? Should I be good? Astound the girl next door with my velvet suit and faustus hood?”)

On Beauty

On Beauty, Smith’s self-described homage to E.M. Forster’s Howard’s End, takes certain themes and motifs and sweeps them into a magnificent novel that both celebrates and (please forgive me, fellow Forster fans) goes beyond its initial inspiration. The family at the center splashes about in a mixture of affection, acceptance, and irritation, sometimes brutal honesty, and also huge secrets: a wild, subversive domesticity.

The book includes a spectacular central party and multiple other gatherings, but daily life in the Belsey family is always a somewhat out-of-control (conflict-filled, intimate) party. In this passage from early in the book, Howard Belsey, a British expat art historian, transplanted to the U.S., has just found out by email that one of his sons is now engaged to the daughter of his biggest academic rival and enemy. He shows it to his wife, Kiki, who doesn’t react as he expected:

“What, Howard? What am I looking at, exactly?” Howard Belsey directed his American wife, Kiki Simmonds, to the relevant section of the e-mail he had printed out. She put her elbows either side of the piece of paper and lowered her head as she always did when concentrating on small type. Howard moved away to the other side of their kitchen-diner to attend to a singing kettle. There was only this one high note – the rest was silence. Their only daughter, Zora, sat on a stool with her back to the room, her earphones on, looking up reverentially at the television. Levi, the youngest boy, stood beside his father in front of the kitchen cabinets. And now the two of them began to choreograph a breakfast in speechless harmony: passing the box of cereal from one to the other, exchanging implements, filling their bowls and sharing milk from a pink china jug with a sun-yellow rim. The house was south facing. Light struck the double glass doors that led to the garden, filtering through the arch that split the kitchen. It rested softly upon the still life of Kiki at the breakfast table, motionless, reading. A dark red Portuguese earthenware bowl faced her, piled high with apples. At this hour the light extended itself even further, beyond the breakfast table, through the hall, to the lesser of their two living rooms. Here a bookshelf filled with their oldest paperbacks kept company with a suede beanbag and an ottoman upon which Murdoch, their dachshund, lay collapsed in a sunbeam.

‘Is this for real?’ asked Kiki, but got no reply. Levi was slicing strawberries, rinsing them and plopping them into two cereal bowls. It was Howard’s job to catch their frowzy heads for the trash. Just as they were finishing up this operation, Kiki turned the papers face down on the table, removed her hands from her temples and laughed quietly.

The voice of the book knows the family as intimately as they know each other. How Kiki reads the paper. Zora’s adoration of pop culture. Breakfast as a dance, the singing kettle and silence, the kitchen, the “dark red Portuguese earthenware bowl faced her, piled high with apples,” a description of the light filling the house so gorgeous that Kiki’s “Is this for real?” seems to refer as much to over-the-top beauty (art, performance art) of the previous paragraph, or even the illusion of a perfect domestic morning, as to Jerome’s letter.

Then, unexpectedly, Kiki laughs. There’s the high drama of what’s happening with Jerome, but also the surprising ways the characters take the multiple big plot turns, and all in prose that offers itself, consciously, as a work of art about works of art.

It’s the anti-Capulets at breakfast, bemused and relatively calm (at least there won’t be any sword-fighting) as they peruse a letter from an offspring errantly in love with the enemy’s child, and it’s also a still life with earthenware bowl and apples.

The Passion

The Passion, also insanely beautiful, is slim, cunning, poetic, and ostentatiously wild. It defies domesticity as it opens with Napoleon in his tent, gorging on whole chicken, the men dedicated to trying to keep up with his appetites. A book of war, romantic and erotic obsession, gambling, and breakdowns. Much of it takes place in Venice, in a dreamlike, feverish atmosphere of murderous, reckless celebration. Winterson has given us a couple of narrators, Henri, an innocent going off to war, and Villanelle, a web-footed boatman’s daughter and casino dealer, thief, and raconteur (“Trust me, I’m telling you stories”). The two of them, in their alternating sections, seem to be speaking directly, intimately, to us as readers who will be amazed and also feel seen.

The whole book is a party, the kind where you might get your heart cut out or lose it all in a wager. Villanelle’s voice moves from dense and lavishly detailed to spare and consciously mysterious. Sometimes she’s letting us in on the party:

Nowadays, the night is designed for the pleasure-seekers and tonight, by their reckoning, is a tour de force. There are fire-eaters frothing at the mouth with yellow tongues. There is a dancing bear. There is a troupe of little girls, their sweet bodies hairless and pink, carrying sugared almonds and copper dishes. There are women of every kind and not all of them are women. In the center of the square, the workers on Murano have fashioned a huge glass slipper that is constantly filled and re-filled with champagne. To drink from it you must lap like a dog and how these visitors love it. One has already drowned, but what is one death in the midst of so much life?

From the wooden frame above with the gunpowder waits there are also suspended a number of nets and trapezes. From here acrobats swing over the square, casting grotesque shadows on the dancers below. Now and again, one will dangle by the knees and snatch a kiss from whoever is standing below. I like such kisses. They fill the mouth and leave the body free. To kiss well one must kiss solely. No groping hands or stammering hearts. The lips and the lips alone are the pleasure. Passion is sweeter split strand by strand. Divided and re-divided like mercury then gathered up only at the last moment.

You see I am no stranger to love.

It’s getting late, who comes here with a mask over her face? Will she try the cards?

This description embodies a disturbing, exhilarating party-going: the marvelous sentences and details create a longing for it, no matter how dangerous it is.

The paragraphs below are more abstract, a concentrated manifesto of the centrality of passion, of love in its wilder forms, a love that costs you everything (a youthful love, I want to say, but having watched enough middle-aged friends throw away domesticity and safety, maybe I should say a youthful state, the desire to gamble everything on intensity):

I have said that behind the secret panel lies a valuable, fabulous thing. We are not always conscious of it, not always aware of what it is we hide from prying eyes or that those prying eyes may sometimes be our own.

There was a night, eight years ago, when a hand that took me by surprise slid the secret panel and showed me what it was I kept to myself.

My heart is a reliable organ, how could it be my heart? My everyday, work-hard heart that laughed at life and gave nothing away. I have seen dolls from the east that fold in one upon the other, the one concealing the other and so I know that the heart may conceal itself.

It was a game of chance I entered into and my heart was the wager. Such games can only be played once.

Such games are better not played at all.

It was a woman I loved and you will admit that is not the usual thing. I knew her for only five months. We had nine nights together and I never saw her again. You will admit that is not the usual thing.

I have always preferred the cards to the dice so it should have come as no surprise to me to have drawn a wild card.

I love the bravado and conundrums of Villanelle’s voice and her assertions: what’s most valuable may lie behind a secret panel, we don’t know our own secrets, we need the beloved to show us what’s concealed even from ourselves, and drawing a wild card is worth everything it costs.

Family parties these days are more subdued, with so many of our loved ones gone. Still accompanied by massive feasting (undimmed, at least for me, by the spreadsheets detailing which of us eats what right now). And then there’s a weekly Geotastic Zoom game night, where some of the geekiest of us guess together whether to drop our pins in Argentina or Western Australia, whether those trees along the road look Finnish, which direction the water seems to be, or if that slightly blurred sign is in Cyrillic.

Though it’s a thrill to teach new books and have no idea what we’ll see in them, it’s another kind of thrill to reread beloved books with marvelous writers and fellow readers. The novelists I’m working with and I have been discovering multiple new angles and aspects to the work. Some books wear out for you. Others keep surprising you, over and over, with their velvet suits and faustus hoods.